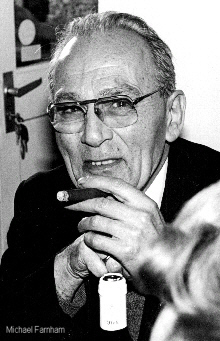

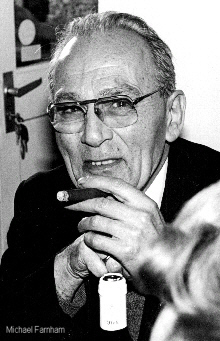

Ted Planas

This article is essentially in three sections. The first is about my own relationship with Ted; the second consists of stories and anecdotes from some of the leading clarinettists who knew him, and the third is a short biography of his early life, written by his son Nick Planas. If anyone has something that they would like me to include, please get in touch.

This article is essentially in three sections. The first is about my own relationship with Ted; the second consists of stories and anecdotes from some of the leading clarinettists who knew him, and the third is a short biography of his early life, written by his son Nick Planas. If anyone has something that they would like me to include, please get in touch.

Ted Planas was without doubt one of the most kind-hearted and generous people I have ever met and everyone who knew him and was helped and encouraged by him would agree. His enthusiasm for music and the instruments themselves was legendary. Most knew him as a technician, though he was also a fine musician, playing clarinets as well as saxophones.

He was particularly skilled at extending existing instruments and the results were outstanding. From working out tone hole positions, sizes etc., to painstakingly making each component individually by hand, the results were of the highest possible standard. If we then consider the circumstances in which this work was done, a cluttered shed in his garden, this achievement is even more admirable. Because of his working methods and because he was regularly interrupted by requests for repairs and advice, these projects took a very long time. And of course, at any moment, if asked to play, the workshop would be immediately closed.

I first heard Ted's name in a telephone call from my old friend, bassoonist John Price, who had recently taken up his position as principal bassoon with the RPO. We had been colleagues in the Ulster Orchestra before John left for London in 1967 and he occasionally rang for a chat. He was very enthusiastic about what Ted had done for him and insisted that I write down his name, so I did, Ted Planners.

Shortly after I moved down to Kingston upon Thames in 1973, a friend pointed out an advertisement in one of the musical magazines saying that Ted was giving a series of free lectures on behalf of the Selmer company up in London, so I went along to one of them. These talks cannot have been advertised very well because I was one of no more than half a dozen people there. Ted's immense enthusiasm was very apparent and he had much to say to fill out the time that had been allocated. Years later, I mentioned this little series of talks to Ted and he said that at the last session only one person turned up and therefore benefited from what was virtually a private lesson with him. The idea was clearly to promote Selmer instruments but, in that sense, can't have been very successful. Every bit as much as another old friend, Brian Manton-Myatt, Ted was a very intense supporter and believer in the quality of Selmer instruments, something which I have never been able to fully understand, to be honest. There will be much more about Brian Manton-Myatt in a future article.

The next person to mention Ted, was Jo McHale. I met Jo when she and I were both clarinet tutors to the Surrey Wind Orchestra in 1975 and 1976. She had a problem with a bass clarinet and wanted to ask Ted's advice about key positions, so I joined her on a visit to Ted's house in Iver Heath, the first time that I'd been there. On that occasion, we were not invited in, but Ted gave advice at his front door. It was perfectly clear that he knew what was required, and although Jo asked him if he would do the work, on this occasion Ted declined.

By the summer of 1976, I had taken up the craft of refacing clarinet mouthpieces and Roy Jowitt, the LSO principal, was one of the players I was trying to help. One of the mouthpieces Roy had given me to work on needed some modifications for which I was not equipped, so I took it along to Ted. He might have worked on the bore, but he certainly changed the angle of the beak. Holding the mouthpiece in a vice and, using a very coarse file initially, he flattened the angle of the beak and then quickly achieved a perfect finish. I was very impressed and Ted would take no money for his work "it didn't take very long", he said. Clearly, if I were to make further progress with my mouthpiece work, Ted was a man who could help.

By the summer of 1976, I had taken up the craft of refacing clarinet mouthpieces and Roy Jowitt, the LSO principal, was one of the players I was trying to help. One of the mouthpieces Roy had given me to work on needed some modifications for which I was not equipped, so I took it along to Ted. He might have worked on the bore, but he certainly changed the angle of the beak. Holding the mouthpiece in a vice and, using a very coarse file initially, he flattened the angle of the beak and then quickly achieved a perfect finish. I was very impressed and Ted would take no money for his work "it didn't take very long", he said. Clearly, if I were to make further progress with my mouthpiece work, Ted was a man who could help.

It quickly became clear that I needed to be able to bore small bore mouthpieces to suit 1010 clarinets and therefore needed reamers to do the job and so I asked Ted if he would show me how to make them. I visited Ted on one or two occasions at around that time and his kindness to me was truly unbelievable. I had clearly got the bit between my teeth at this point and wanted to pick up as much as I could from him. The visit I most particularly remember started out one evening, which we spent in his little wooden shed in the garden, when I asked him about the things that I would need to make progress. Time passed by very quickly as Ted pointed out many things that would be of assistance. After what seemed like a fairly short time he said "that'll be the dawn chorus": we had been talking literally all night! I went home, tried to grab a few hours' sleep before going up to Buck & Ryan's shop near Tottenham Court Road to buy tools and then on to visit the Walsh shop near Hatton Garden, to buy raw materials, like polishing compounds. Shortly afterwards I bought my first lathe and made my first reamers. All these years later, those same reamers are still the ones I use to cut the bores of my mouthpieces. I was now up and running, producing mouthpieces, with immense gratitude to Ted for helping me on my way.

When I first started producing clarinets, in conjunction with Tony Ward and Derek Winterbourn in 1982, I was again enormously grateful for Ted’s help. He showed me how to make undercutting tools and, as with the mouthpiece reamers, those early cutters are still in regular use. Still later, following my acquisition of parts and production equipment from Boosey & Hawkes in 1986, his help was again invaluable. I needed to make up something to hold the end of the bells in the lathe, when cutting the inside profile. Ted showed me his solution, which was made from a car clutch plate. As soon as I could, I dashed around to our local Motorists Discount Centre where exactly the right thing was being sold off. I also needed a jig for drilling pillars for the screws, when in position on the clarinet. There was one at B&H but for some reason they would not let me take it. So, Ted asked me to get hold of the raw materials, which I delivered to him, and he then took immense trouble to make one for me. How I would have found solutions to those problems without his help I simply do not know.

Another vital component in the manufacture of clarinets is of course seasoned wood. Ted mentioned that he had a large stock of it stored in his loft, which he kindly sold to me. This included some extra-long pieces which I eventually used for my basset clarinets. This was of outstanding quality and certainly contributes to the success of our bassets.

Perhaps Ted saw something in me that was worth encouraging, but he offered that level of encouragement to absolutely everyone.

In 1986 I took Gervase de Peyer to meet Ted. As always, we were led into the kitchen. There were the usual greetings, Ted mentioning that he and Gervase were about the same age. Gervase said that he wasn't sure but thought that Ted looked younger. This was shortly after Gervase had put aside his B&H 1010s and changed to my instruments. There is no doubt that his A was outstanding and still is but the B-flat paled in comparison. Sometime later, Gervase and Ted must have met up again when Gervase asked Ted if he could thin the walls on the outside of the his B-flat because that was the only difference he could see between the B-flat and the A. The idea was absolute nonsense of course. Ted probably tried to talk sense into Gervase, who's playing he did not admire I'm afraid, and sensibly refused to do the work. I remember Gervase later referring to Ted, somewhat acidly, as "that Italian". On a subsequent visit it was clear that Ted's wife Barbara had been impressed by Gervase, mentioning his visit with pride. Ted was not enamoured by Jack Brymer's playing either, "a café player, always was" although Jack spoke very highly of Ted. And yet Ted was good friends and an admirer of Roy Jowitt, Jack’s pupil, colleague, and a player of similar style. They had a mutual enthusiasm for clarinets and cycling. How is that anomaly explained?

In 1986 I took Gervase de Peyer to meet Ted. As always, we were led into the kitchen. There were the usual greetings, Ted mentioning that he and Gervase were about the same age. Gervase said that he wasn't sure but thought that Ted looked younger. This was shortly after Gervase had put aside his B&H 1010s and changed to my instruments. There is no doubt that his A was outstanding and still is but the B-flat paled in comparison. Sometime later, Gervase and Ted must have met up again when Gervase asked Ted if he could thin the walls on the outside of the his B-flat because that was the only difference he could see between the B-flat and the A. The idea was absolute nonsense of course. Ted probably tried to talk sense into Gervase, who's playing he did not admire I'm afraid, and sensibly refused to do the work. I remember Gervase later referring to Ted, somewhat acidly, as "that Italian". On a subsequent visit it was clear that Ted's wife Barbara had been impressed by Gervase, mentioning his visit with pride. Ted was not enamoured by Jack Brymer's playing either, "a café player, always was" although Jack spoke very highly of Ted. And yet Ted was good friends and an admirer of Roy Jowitt, Jack’s pupil, colleague, and a player of similar style. They had a mutual enthusiasm for clarinets and cycling. How is that anomaly explained?

Nick Planas offered this observation on Ted’s relationship with Jack Brymer:

I don't know why he had such a beef with Jack Brymer who was simply known as Brymer whenever mentioned. The one time I met Jack I was on an emergency repair run. Jack was recording at Maida Vale and his soprano sax gave out. He rang Ted in a bit of a panic, and I had just got home from my part-time job on the Underground. I was immediately dispatched by taxi to Uxbridge with Ted's own soprano and took the tube to Maida Vale. I think Jack thought I was just a messenger boy, but he was very good to me and greatly relieved to hand his instrument for me to take back to be repaired. I know Ted put as much effort into that as he would into anything else.

Ted enjoyed telling a story about a telephone call from Switzerland which Barbara initially took, saying that it was from someone called Stadler. Ted said, it can't be him he's dead! In fact, the call was from renowned Swiss clarinettist Hans Rudolf Stalder who had borrowed an historical clarinet from a museum and had broken part of it. I'm not sure, but it might have been the crook of a lower pitched instrument. Clearly Ted's reputation as a technician was worldwide and Stalder wisely asked for his help. With immense trouble, Ted managed to repair the break invisibly, with steel pins made from bike spokes I believe. When the instrument was placed back on display at the museum, an X-ray of the repair sat with it. I wonder if it still does?

Keith Puddy telephoned to give these memories of Ted:

Ted made a copy of a very rare and valuable historic instrument for me. He copied it beautifully, although incorporating some of the adjustments that had subsequently been made to it, which I had to get corrected. Ted hand-made several mouthpieces for me, usually from boxwood or occasionally blackwood. One was particularly useful, which I played successfully on several different historic instruments, with good intonation, because of the flexibility that the mouthpiece offered. There was an unfortunate occasion when Ted was making yet another mouthpiece from solid wood for me when a fellow professional knocked on the door, disturbing Ted. There was an accident with the mouthpiece and Ted had to start again!

Another famous recipient of his generosity, probably in the 1950s or 1960s, was Bernard Walton, renowned principal clarinet with the Philharmonia Orchestra for many years. Bernard played on a pair of Schmidt clarinets that were chosen for him by his teacher George Anderson many decades earlier. Bernard was devoted to these instruments, though Jack Brymer described them as "an acoustical travesty". Understandably, the keywork was showing considerable signs of wear and so Ted fitted phosphor bronze inserts into the ends of the keys to stabilise them. This would have been a very tricky procedure, but no doubt Ted brought it off to perfection. Bernard sent a cheque in grateful thanks, but Ted simply returned it, not wanting to take anything from the great man.

Ian Herbert, renowned principal clarinet with the Royal Opera House, shared these reminiscences of Ted.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Ted Planas was in constant demand for his extensive skills as a worker of miracles in the repair and improvement of many woodwind instruments, mostly clarinets. Players from other countries would seek his advice. He had always been a strong advocate of Selmer clarinets, and those were his instruments of choice. On numerous occasions he came to play with us in the ROH pit. There were two incidents which stand out for me. A member of the section had a problem with her keywork during a ballet matinee. Ted took her clarinet, removed one of his shoes and gave the offending key a sharp whack and handed it back to its owner: it worked. On another occasion, Ted was deputising as second clarinet in a performance of Der Rosenkavalier with George Solti. This was quite an undertaking for Ted, who would not have seen this opera before. Solti, realizing the problem, came across to our stand and said "Mr. Herbert, if your colleague is at any time asleep, just give him a sharp elbow in the ribs." Solti had quite a sense of humour.

John Payne, also distinguished principal clarinet at the Royal Opera, offered a few anecdotes.

John Payne, also distinguished principal clarinet at the Royal Opera, offered a few anecdotes.

My first experience, though I didn't meet him, was when I was in the NYO. I was 16 and had a split in my top joint, the first of several throughout my life, Thea King contacted Ted and arranged a repair. To get it to him I had to take it at the end of an NYO course to Richmond Theatre where he was working. I took the tube from King's Cross to Richmond on my own, a young lad from Leeds, astonished by the length of time it took and when I found the theatre I approached the commissionaire at the front entrance and explained the situation. He went to look for Ted. I had no idea of what time he was likely to be there, what time the shows were, etc, but he came back to tell me Ted wasn't there that day but, if I left the instrument with him, he would see that Ted got it. This I did and, in a week or so, the instrument arrived back in Leeds duly pinned. I was very trusting, but my trust was clearly well-placed.

He was always hugely entertaining on-stage band evenings, with loads of anecdotes. In those days if you were in a stage band in an opera like Traviata or Macbeth, where you make a couple of appearances with long gaps, you could go to the pub in between and have a very convivial evening. This is completely verboten these days on pain of dismissal.

One story was when he was doing the Wembley Ice Show and the other clarinet player complained that there was something wrong with his instrument, which was badly out of tune. Ted quickly spotted he'd mixed up the A and Bb joints. Unfortunately, the other player had lent the A clarinet to a pupil to play the Mozart concerto!

On another occasion I asked him to shorten a mouthpiece for me which Ian had given to me. Unfortunately, when he was shortening it, it flew out of the lathe chuck and the tip was chipped. He apologised profusely, mended it so you couldn't see the repair but made another mouthpiece out of rod ebonite. I still have it. It has a very good sound, though I never used it much. "I'm a mouthpiece maker, not a mouthpiece finisher!" was Ted's comment.

He used to play soprano saxophone in a piece by Koechlin we used to do for the ballet. It was a horrible piece and there was a point where the soprano sax was suddenly left alone with a short phrase which ended with a large leap to a very high note. Ted could never get this and squawked every time leaving the rest of us with shoulders heaving and tears streaming down our cheeks, unable to play for the next few bars. It perhaps seems mean to mention this, but it was hilarious in the context of the terrible music. Fortunately, Ted seemed not to mind.

I remember his shed and the room in his house stacked to the ceiling with instrument cases. I was there once telling him about my first teacher, George Threlfall, in Leeds. Mr. Threlfall, as I still think of him, had made a couple of alterations to his 1010s. One was to lengthen the throat G# key to make trilling G# to A easier and the other, more drastic alteration, was to cut off the speaker tube flush with the bore, something which he encouraged me to do on my Emperors. A clarinettist friend who was with another teacher mentioned this to his teacher who said "what Threlfall knows about the clarinet could be written on the head of a pin!" As I was relating this to Ted, he pointed to a case on the floor, "open that" and there were those self-same instruments, easily identifiable by their unique features. Ted had them there for overhaul.

Ted was one of those characters who made the social side of playing professionally such fun and so interesting.

Daniel Bangham writes about Ted's involvement in education.

Ted Planas was the "end of course" adjudicator for Newark students for several years. This involved a short lecture by him to the students and then he judged their standard of work. If time had permitted, he could have taught them a lot more as his experience was encyclopedic.

For his last visit I collected him from Iver Heath and took him to Newark for the day. He then stayed with us in Cambridge and visited my workshop the next day. We then spent the morning discussing mouthpiece adjustment and design before returning him back to London. We had been friends and collaborators since we worked on my first period bassett clarinet in the 1980's. My memory is of his restless enthusiasm and a willingness to educate. There were, of course the endless Gauloises cigarettes and an ever-ready laugh.

Many years ago, John Denman told of an occasion when Ted demonstrated his immense courage, a quality which would not surprise anyone who knew him. John and Ted were travelling back from a playing job when they entered the Piccadilly underpass. The car in front of them hit the wall, tipped onto its side, and caught fire. Ted immediately leapt out of the passenger seat and, like a weightlifter, dragged the two hysterical teenage girls away from the burning car, their clothes on fire. Ted, although visibly shaken, declined to give his name to the police. When returning to John’s car, they realised that Ted’s hands, arms and legs were blistered and burnt, his hair singed. Typically, he refused treatment, saying that he would take care of himself. He saved those girls lives, and they never knew who he was.

We all tend to assume that Ted never needed any advice or assistance himself, but this was not so. A near neighbour in Iver Heath was described by Ted as his “tame engineer”, presumably a man of great knowledge and experience, whose advice was occasionally called for and appreciated.

Ted always looked to the future of clarinet design, rather than backwards. He was not particularly enamoured by the authentic instrument movement, though he did a lot to help those who were. He was a great enthusiast for the Marchi clarinet. This model offered exciting possibilities in some ways but the keywork was inevitably very complex, though that would never have been a problem for Ted of course. He was very proud of his association with the Marchi, saying "this is now my clarinet", i.e. his number one B-flat instrument.

Ted's close friend Steve Trier said that he was occasionally depressed. I never saw any of this myself, just his immense enthusiasm and generosity. He had very high standards and probably hoped that others would follow his lead, but he must occasionally have been disappointed. I know of at least two well-known professionals who were, in Ted's words, "forbidden this house". I know that one of them argued about payment for Ted's work. In most cases, players tried hard to get Ted to take more money than he had asked for, but on this occasion it was clearly the other way around.

Ted's way of life, including whiskey, coffee and cigarettes as well as the expenditure of all that nervous energy, must have taken its toll on his health and demeanour and so his playing suffered. One player in a leading London orchestra said that Ted's standards were no longer high enough and so he was increasingly obliged to take lower-level work.

He felt very strongly that "knowledge is for dissemination" but in the musical instrument business there is inevitably a tendency to hold onto trade secrets. My old friend Brian Manton-Myatt's attitude was exactly the same as Ted's, so every time I think of Ted or Brian, I am reminded of this. Ted was fully aware of the significance of his knowledge and the quality of his work in this field and, on one occasion, when particularly pleased with an outcome, said to me "how about that job in Paris now!"

The news of Ted's passing in the summer of 1992 was one of great sadness for the whole of the clarinet community who knew him. In the autumn of that year, Keith Puddy hosted a gathering in his memory which was attended by many eminent musicians but also by amateur players who played side-by-side Ted in amateur wind bands.

Ted always wanted to be remembered simply as "a musician" but, for those of us privileged to know him, he was that and so much more.

The news of Ted's passing in the summer of 1992 was one of great sadness for the whole of the clarinet community who knew him. In the autumn of that year, Keith Puddy hosted a gathering in his memory which was attended by many eminent musicians but also by amateur players who played side-by-side Ted in amateur wind bands.

Ted always wanted to be remembered simply as "a musician" but, for those of us privileged to know him, he was that and so much more.

A short biography of Ted's earlier life by his son Nick Planas.

Pop was born Edward Planas in New York on 25th March 1924 to Eduardo Jose Planas, an automotive electrical engineer, and Dolores Hales, the daughter of a Tobago plantation owner. His father was born in Barcelona in 1899 but became a naturalized American citizen and was known as Eddie, while the young Edward was christened with the additional middle name of Gordon, which both his parents used to know him by.

In 1927 his younger brother Richard (Dickie) was born, but not long after that the marriage broke down, and in early 1929 Dolores took the children back to Trinidad, where Eddie Planas had been brought up, and where his mother still lived. Less than a week after they arrived, both children caught meningitis and sadly Dickie died aged 2. Ted was ill but recovered fully in due course. He never saw his father again although they did correspond from time to time.

Meantime, his mother remarried to an Englishman, Sydney George Preece, whose family were from Maidenhead. When Ted was 9, they moved back to England, living in a newly built house on Bridle Road, Maidenhead. When Ted was 13 his mother was killed in a terrible car crash on the Colnbrook by-pass, when the car, driven by Sydney, ran into the back of a lorry which had broken down and was unlit. The crash also killed Sydney's parents and seriously injured his sister as well as himself. This tragedy left a hole in Ted's life and so he rarely reminisced about his teenage years. He continued to live with the large Preece family, but he never forgave his stepfather for the loss of his mother, and as soon as he reached his 18th birthday he moved out of the family home for good.

One thing that I'm curious to know is how he became so musically proficient so quickly. Someone in the Preece family circle must have encouraged his music and, although he denied playing the piano, I have a school report which shows he clearly did. He went to Loughborough College to study aero-engineering in September 1939. He was only 15 but I found him there on the 1939 Register, a one-off government census of all non-military personnel.

One thing that I'm curious to know is how he became so musically proficient so quickly. Someone in the Preece family circle must have encouraged his music and, although he denied playing the piano, I have a school report which shows he clearly did. He went to Loughborough College to study aero-engineering in September 1939. He was only 15 but I found him there on the 1939 Register, a one-off government census of all non-military personnel.

On hearing a recording of Artie Shaw playing the clarinet he decided there and then that he wanted to learn it. Before he could take delivery of his new instrument, he got a broomstick and put Sellotape around it where the holes were so, by the time he took delivery he already knew the basic fingerings. One of his Preece step-uncles was a gambler and sold this clarinet without telling Ted, to pay off a debt. Although it was replaced straight away by his stepfather, Ted was incensed; this was another nail in the coffin of his relationship with the family.

By 1943 he was studying at the Royal Academy of Music with George Anderson, as well as Albert Goossens and W J "Billy" Matthews privately. He was a contemporary of comedian Mike Winters, and great pals with Johnny Dankworth and they got up to all sorts of mischief, which continued after they had graduated. Ted, being an American by birth, was drafted into the US Army in 1946 and stationed in Germany, where he found his US pay to be a great advantage on the war-torn continent. Stationed in Frankfurt, he could 'nip' down to Paris, where he took additional lessons with Ulysse Delecluse, who once wrote to us that Ted "could really fly around the clarinet". He was able to buy instruments and bring them back to England (legally) although I am aware of another activity which was slightly less above board. According to my mother Barbara, Ted would buy brand new German cameras and bring them back to England and Johnny Dankworth would find an outlet for them in a London camera shop. I'm not sure of the exact details and so I wouldn't want to implicate JD in any of this, but it does sound par for the course.

Home

Clarinets

Mouthpieces

Players

Peter Eaton

New Articles

CASS Articles

Clarinet Care

Prices

Overhauls

Contacts

Links

This article is essentially in three sections. The first is about my own relationship with Ted; the second consists of stories and anecdotes from some of the leading clarinettists who knew him, and the third is a short biography of his early life, written by his son Nick Planas. If anyone has something that they would like me to include, please get in touch.

This article is essentially in three sections. The first is about my own relationship with Ted; the second consists of stories and anecdotes from some of the leading clarinettists who knew him, and the third is a short biography of his early life, written by his son Nick Planas. If anyone has something that they would like me to include, please get in touch.

By the summer of 1976, I had taken up the craft of refacing clarinet mouthpieces and Roy Jowitt, the LSO principal, was one of the players I was trying to help. One of the mouthpieces Roy had given me to work on needed some modifications for which I was not equipped, so I took it along to Ted. He might have worked on the bore, but he certainly changed the angle of the beak. Holding the mouthpiece in a vice and, using a very coarse file initially, he flattened the angle of the beak and then quickly achieved a perfect finish. I was very impressed and Ted would take no money for his work "it didn't take very long", he said. Clearly, if I were to make further progress with my mouthpiece work, Ted was a man who could help.

By the summer of 1976, I had taken up the craft of refacing clarinet mouthpieces and Roy Jowitt, the LSO principal, was one of the players I was trying to help. One of the mouthpieces Roy had given me to work on needed some modifications for which I was not equipped, so I took it along to Ted. He might have worked on the bore, but he certainly changed the angle of the beak. Holding the mouthpiece in a vice and, using a very coarse file initially, he flattened the angle of the beak and then quickly achieved a perfect finish. I was very impressed and Ted would take no money for his work "it didn't take very long", he said. Clearly, if I were to make further progress with my mouthpiece work, Ted was a man who could help. In 1986 I took Gervase de Peyer to meet Ted. As always, we were led into the kitchen. There were the usual greetings, Ted mentioning that he and Gervase were about the same age. Gervase said that he wasn't sure but thought that Ted looked younger. This was shortly after Gervase had put aside his B&H 1010s and changed to my instruments. There is no doubt that his A was outstanding and still is but the B-flat paled in comparison. Sometime later, Gervase and Ted must have met up again when Gervase asked Ted if he could thin the walls on the outside of the his B-flat because that was the only difference he could see between the B-flat and the A. The idea was absolute nonsense of course. Ted probably tried to talk sense into Gervase, who's playing he did not admire I'm afraid, and sensibly refused to do the work. I remember Gervase later referring to Ted, somewhat acidly, as "that Italian". On a subsequent visit it was clear that Ted's wife Barbara had been impressed by Gervase, mentioning his visit with pride. Ted was not enamoured by Jack Brymer's playing either, "a café player, always was" although Jack spoke very highly of Ted. And yet Ted was good friends and an admirer of Roy Jowitt, Jack’s pupil, colleague, and a player of similar style. They had a mutual enthusiasm for clarinets and cycling. How is that anomaly explained?

In 1986 I took Gervase de Peyer to meet Ted. As always, we were led into the kitchen. There were the usual greetings, Ted mentioning that he and Gervase were about the same age. Gervase said that he wasn't sure but thought that Ted looked younger. This was shortly after Gervase had put aside his B&H 1010s and changed to my instruments. There is no doubt that his A was outstanding and still is but the B-flat paled in comparison. Sometime later, Gervase and Ted must have met up again when Gervase asked Ted if he could thin the walls on the outside of the his B-flat because that was the only difference he could see between the B-flat and the A. The idea was absolute nonsense of course. Ted probably tried to talk sense into Gervase, who's playing he did not admire I'm afraid, and sensibly refused to do the work. I remember Gervase later referring to Ted, somewhat acidly, as "that Italian". On a subsequent visit it was clear that Ted's wife Barbara had been impressed by Gervase, mentioning his visit with pride. Ted was not enamoured by Jack Brymer's playing either, "a café player, always was" although Jack spoke very highly of Ted. And yet Ted was good friends and an admirer of Roy Jowitt, Jack’s pupil, colleague, and a player of similar style. They had a mutual enthusiasm for clarinets and cycling. How is that anomaly explained? John Payne, also distinguished principal clarinet at the Royal Opera, offered a few anecdotes.

John Payne, also distinguished principal clarinet at the Royal Opera, offered a few anecdotes. The news of Ted's passing in the summer of 1992 was one of great sadness for the whole of the clarinet community who knew him. In the autumn of that year, Keith Puddy hosted a gathering in his memory which was attended by many eminent musicians but also by amateur players who played side-by-side Ted in amateur wind bands.

Ted always wanted to be remembered simply as "a musician" but, for those of us privileged to know him, he was that and so much more.

The news of Ted's passing in the summer of 1992 was one of great sadness for the whole of the clarinet community who knew him. In the autumn of that year, Keith Puddy hosted a gathering in his memory which was attended by many eminent musicians but also by amateur players who played side-by-side Ted in amateur wind bands.

Ted always wanted to be remembered simply as "a musician" but, for those of us privileged to know him, he was that and so much more. One thing that I'm curious to know is how he became so musically proficient so quickly. Someone in the Preece family circle must have encouraged his music and, although he denied playing the piano, I have a school report which shows he clearly did. He went to Loughborough College to study aero-engineering in September 1939. He was only 15 but I found him there on the 1939 Register, a one-off government census of all non-military personnel.

One thing that I'm curious to know is how he became so musically proficient so quickly. Someone in the Preece family circle must have encouraged his music and, although he denied playing the piano, I have a school report which shows he clearly did. He went to Loughborough College to study aero-engineering in September 1939. He was only 15 but I found him there on the 1939 Register, a one-off government census of all non-military personnel.